My dissertation offers a fine-grained study of the lived experiences and consequences of hate crimes against American religious minorities. Through a comparative analysis of the aftermath of attacks on the oldest Jewish congregation on the West Coast and a newly established Muslim community in southwestern Missouri, I examine the reconstructions of place, collective memory, and communal identity after violence to places of worship. At the heart of my study is a concerned curiosity about the consequences of an attack on a religious space for its community.

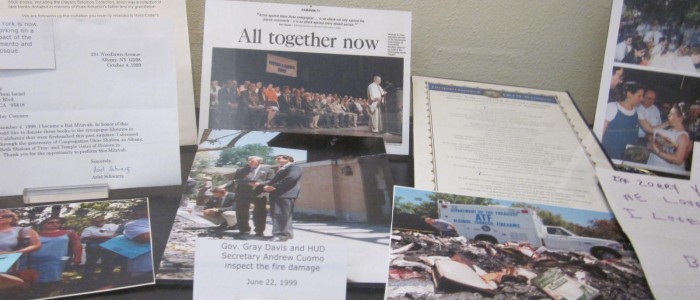

As the sun rose on June 18, 1999, blackened scraps of paper floated past the building’s charred skeleton through warm stilled summer air. Congregation B’nai Israel, the oldest congregation west of the Mississippi, was one of three synagogues in Sacramento, California left smoldering that Friday morning. No one was injured, but the synagogue sustained heavy damages to its sanctuary and the total destruction of its library. Even after the perpetrators were arrested and sentenced, communal recovery from the fires had barely begun. Rebuilding and the massive funding effort it required seemed relatively minor setbacks compared with the loss articulated by a Sacramento Jewish leader in an article in the Los Angeles Times. “What can’t be replaced,” he lamented, “is peace of mind.”

Over a decade later, in the early hours of August 6, 2012, the imam of the local Islamic Society faced the flaming wreckage of his community’s mosque in Joplin, Missouri. By the time the fire was extinguished, the mosque had been leveled. Amidst piles of debris, pulpy sodden mounds revealed the matted remains of prayer rugs and copies of the Qur’an. No one was injured, but the damages were immense. Backed by support from the Joplin community, the imam stated in an interview that, “it is hard, but we survive.” The Islamic Society formed a temporary prayer space in a former Thai restaurant in a strip mall. The community struggled to accrue the funding to build a new mosque, finally relocating to it by the end of Ramadan in 2014.

In what ways do religious places and people bear memories of trauma – or is violence effaced entirely from physical and emotional landscapes? Although the hate crimes are part of the historical pasts of Congregation B’nai Israel and the Islamic Society of Joplin, these communities’ memories of violence and processes of repair continue to shift and evolve. This research explores the ways in which victimized religious minorities negotiate past and present, arson and reconstruction, place and people. Uncovering the religious, social, and political ramifications of arson, I argue that these moments of violence served as catalysts that compelled religious groups to re-evaluate their religious priorities, their collective aspirations, and their relationships to their local communities.